Struggling with outdated change management approaches? You’re not alone! Traditional change management was designed for organizations of the past, not our more diverse, empowered, and human-centric organizations of today.

This blog post is excerpted from The Strategy Activation Playbook: A Practical Approach to Bringing Your Strategies to Life, by Aric Wood. Slated for release in September 2022, the book is available for pre-order here.

Our current approach to leading change in organizations didn’t happen by accident—it was the product of the era in which most management thinking developed.

We must look to history to understand how we got here. The modern organization is rooted in military history—at the time, the most efficient model for coordinating large groups of people to achieve strategic objectives. Though groups of humans have been collaborating throughout history, warfare hatched the first large-scale mobilization and coordination of resources united in an organizational structure. It has been present as a model for at least 10,000 years.

As we entered the Industrial Age, which required large groups of people working in a coordinated way, it was natural to leverage the military model as the most efficient model for corporate organizational structure.

Most managers had risen from the ranks of military experience, further entrenching military discipline and norms throughout the emerging corporate structure. This remained true through the formation of the modern business schools, whose coming of age occurred on the heels of World War II.

The impact of these influences remains today. It shows up in the language of business, for example – think of all the business jargon that clearly has military roots. Our actions are defined by missions, strategies, and tactics, which we roll out at all-hands meetings. In marketing, we defend our position to ensure that we don’t lose ground. To capture market share, we might use guerilla marketing. We talk about the chain of command, including leadership ranks and their subordinates, the boots on the ground and their frontline managers. We give people promotions and honor their years of service. Even my own business school was organized into cohorts—a structure modeled after the Roman legions.

Historically, men predominantly led and populated armies, lending not only an overtly military language to business but also a masculine one, impacting not only the words of business but also its culture. The structure favored men, creating a highly homogenous workforce, which was hostile to diversity of all types, especially women. Theses impacts are also still apparent, with 94% of current Fortune 500 CEOs being male and 68% of those being white.1

As a result, we’ve been trained to think of organizations as homogenous and mechanistic, with a clear set of rules, a command-and-control structure, and the ability to leverage hierarchy to get things done quickly by issuing top-down directives to reallocate resources to meet objectives.

The metaphor of the organization as a machine becomes apparent – an easily programmable structure that will run the “program” that we define, and then pivot in a new direction as soon as we provide new instructions.

By and large, this was true up until the end of the 20th century. The corporate structure and the needs of the organization were tantamount, and the individuals in the system were seen as “human resources” – in effect a cog in the wheel of the machine, easily replaceable when they wore out.

This was easier to maintain with a homogenous workforce, leaders trained in the command-and-control mindset, and a prevailing system stacked in favor of the employer. For most of modern history, this was the context that ruled the world of work.

What changed? A number of factors:

The influence of military tradition is on the retreat

The untangling of the military from modern organizations is accelerating, and its influence is waning. When President Dwight Eisenhower described the intersection of military and corporate entities as the military-industrial complex in his farewell address of 1961, military spending represented 9% of the U.S. economy. Today, that has shrunk by two-thirds to 3 percent, driven by reduced peacetime spending, technological efficiencies of scale, and privatization.2

In addition to the military playing a smaller part in our overall economy, it also employs significantly fewer people and plays a much smaller part in the grooming of our leadership ranks (pardon the military jargon). According to research by Benmelech and Frydman, as recently as 1980, 59 percent of the CEOs of large public corporations had served in the military. By 2013, only 6 percent were led by CEOs with military experience.3

As a result, the influence of structure, process, language, and behaviors rooted in the military experience are waning in our organizations, creating space for new ways of being and a proliferation of different models of organizational design and management.

The modern workforce has greater power and increased protections

While labor revolts like the peasant revolts in medieval England have occurred throughout history when workers rise up to fight for fair working conditions, the Industrial Age elevated this to a human rights issue at a scale too large to ignore.

Though power was once universally in the hands of employers, in the last century global labor rights movements have shifted the balance of power towards employees.

This was accelerated by the advent and influence of global organizations. In 1919, the International Labour Organization (ILO) was formed as part of the League of Nations to protect workers’ rights, and this organization was later incorporated into the United Nations.

Under the United Nations, several workers’ rights were described and incorporated into two articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, which has now been signed by 192 nations.

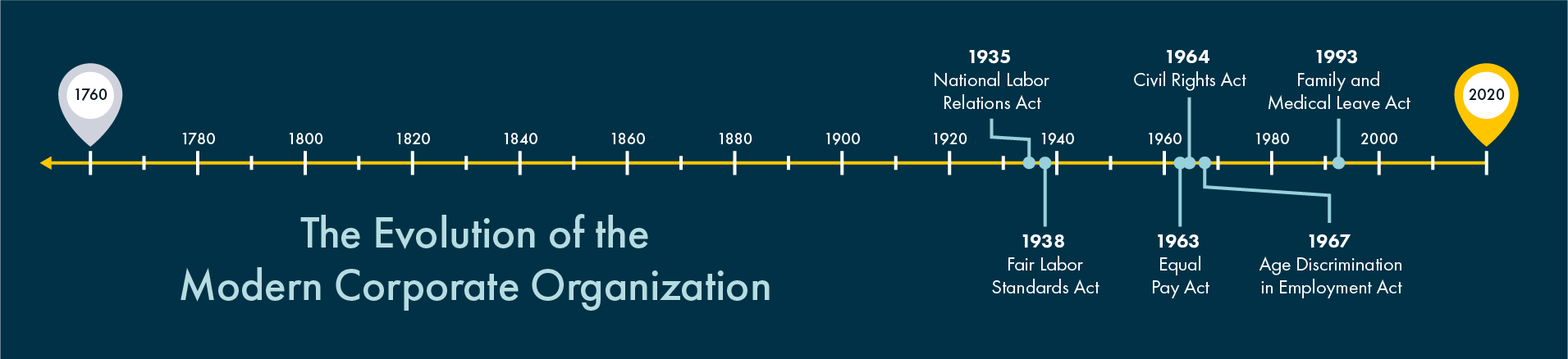

While we may take these changes for granted, it is important to understand that it’s been less than a century since these rights were acknowledged, let alone implemented. In the United States, for example:

- It wasn’t until 1935 that the National Labor Relations Act enshrined labor rights in the nation.

- It wasn’t until 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act first made accommodations for the establishment of an eight-hour workday, time-and-a-half pay for overtime, and clear limitations around child labor.

- It wasn’t until 1963 that the Equal Pay Act sought to abolish wage disparity between genders.

- It wasn’t until 1964 that the Civil Rights Act banned discrimination based on race.

- It wasn’t until 1967 that the Age Discrimination in Employment Act created protections for older workers.

- It wasn’t until 1993 that the Family and Medical Leave Act ensured that workers have job-protected (but unpaid) leave for qualified medical and family reasons.

Let’s pause to realize how recent these changes are. If we consider the era of the modern corporate organization to have begun around 1760, at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, we have only recently seen these significant shifts in the balance of power between employers and employees.

These changes paved the way for the organization to become less of a machine and more like an organism: in balance, with employees empowered as stakeholders in the system. While we have a long way to go, it makes sense that these shifts require us to consider how our old systems of managing change need to change.

The modern workforce is less homogenous

Our workforce is more diverse than it has ever been, and this shift is accelerating as the structures of homogeny are being actively removed.

Women’s share of the labor force has undergone a major transformation since 1950. The share of women in the labor force grew from 30 percent in 1950 to almost 47 percent in 2000, and is projected to be above 48% by 2050.4

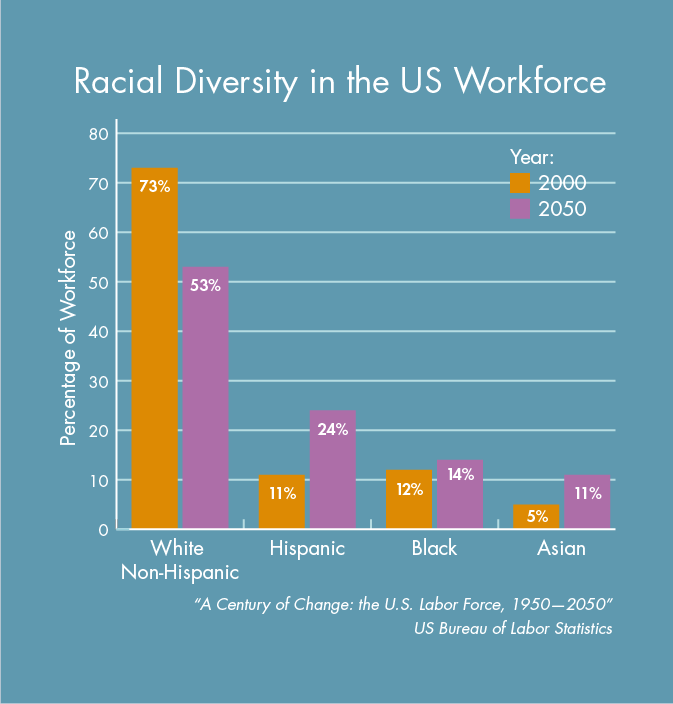

Racial diversity is also increasing more rapidly than ever. According to research4:

- The share of white non-Hispanics is anticipated to decrease from 73 percent in 2000 to 53 percent in 2050.

- Meanwhile, Hispanics are expected to more than double their share of the labor force, from 11 percent in 2000 to 24 percent in 2050.

- Blacks also are expected to increase their share from 12 percent in 2000 to 14 percent in 2050.

- Asians, the fastest-growing group in the labor force, are projected to increase their share from 5 percent to 11 percent between 2000 and 2050.

This increasing diversity is occurring across many dimensions. Workforces are increasingly comprised of individuals of different genders, religions, races, ages, ethnicities, sexual orientations, education, and lived experiences, resulting in dramatically less homogenous organizations.

The Big Shift

But the above shifts are part of a much bigger change taking place in business. While each and every one of them has contributed to the shift in our current context, there’s also a larger story to tell.

Probably most transformational, the very basis of competition has shifted in the modern world: from productivity, efficiency, and output to creativity, innovation, and purpose.

The business models that we're operating are trailing the era in which we live today.

Aric Wood

The systems we live and work in were designed in the past. They were created to serve the Industrial Age, which valued productivity, efficiency, and return on capital above all. The systems did the job they were supposed to do, but they didn’t anticipate where we were headed: into an age where human creativity is the most valuable resource.

Klaus Schwab, executive chairman of the World Economic Forum and author of the book The Fourth Industrial Revolution, states: “I am convinced of one thing—that in the future, talent, more than capital, will represent the critical factor of production.”5

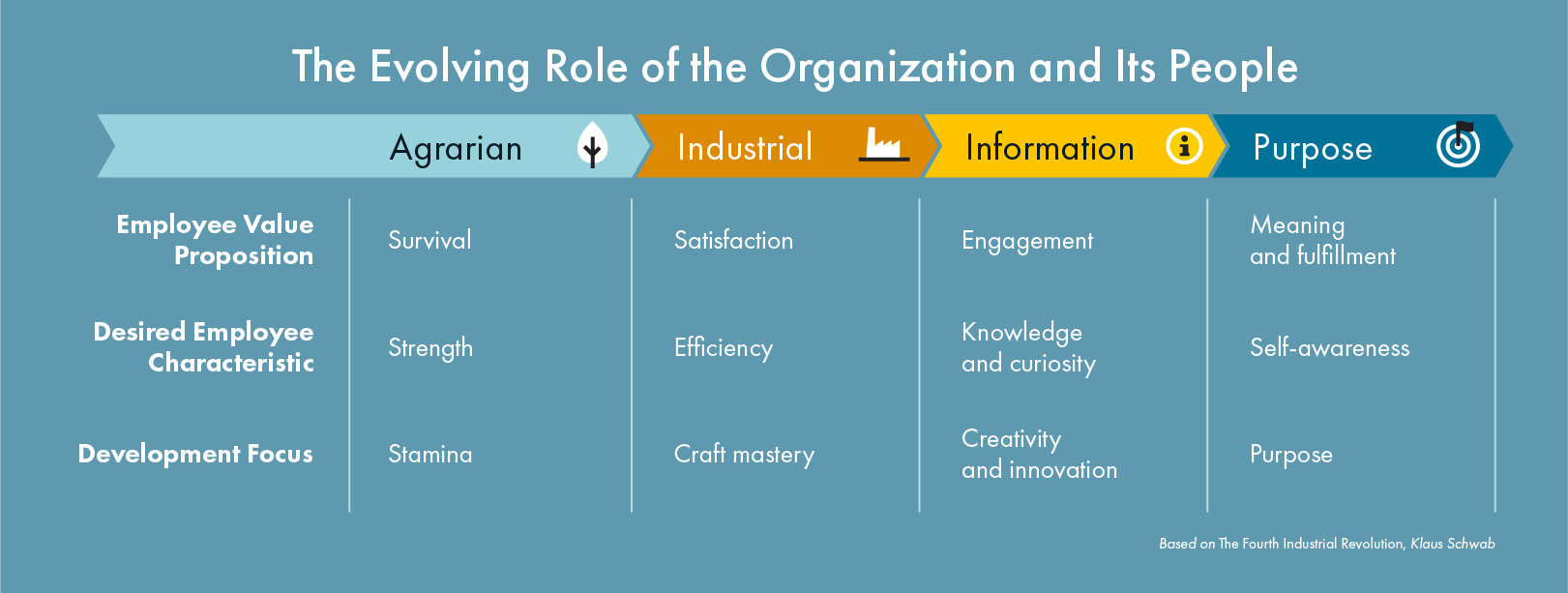

Schwab and others who are tracking the history of the organization point to why employee engagement and investment in activation to achieve change has become so important. We can think of the history of the organization as occurring in four broad ages:

- The Agrarian Age: As humans began to grow their own food, they began to form cooperative partnerships to distribute labor. The primary basis of competition was strength and stamina, and the organizational structure was small groups of individuals with shared interests.

- The Industrial Age: In the 18th century, as trade provided access to a diversity of natural resources, technology improved and capital was consolidated to create entities that could increase the value of basic resources. Labor became a commodity in service of capital. The basis of competition was efficiency and overall organizational output, with the organization relying on a subservient labor structure.

- The Information Age: Beginning in the 1970s, it became more profitable to add value to information than to natural resources. While both models coexisted, a shift began in the role humans would play in the organization of the future. The emerging basis of competition was creativity and innovation, requiring a flexible organizational structure and an empowered workforce. And even though we’re only just catching up to that reality, we’re already moving into the next age:

- The Purpose Age: As improved quality of life becomes more accessible for more humans and basic needs are met with the help of the technological advancements of the Information Age, organizations shift to serving humans wants and needs more effectively. As a result, self-awareness and empathy become more important, with an emerging organizing structure based on self-selection around a common purpose.

As we look at the evolution of business over time, it becomes apparent what’s happening: The business models we’re operating under are trailing the era in which we live today. Our structures have remained largely remnants of the Industrial Age, even as we’ve been living in the Information Age. And while we’re catching up to that shift, we are yet again already moving into the next age – Purpose.

As leaders, we need to take a longer perspective on what’s happening around us to anticipate the direction of change and begin building new approaches today to guiding change in our organizations tomorrow.

Sources:

- “Women CEOs of the S&P 500,” Catalyst, August 30, 2021, https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-ceos-of-the-sp-500/

- Loren Thompson, “Eisenhower’s ‘Military-Industrial Complex’ Shrinks to 1% of Economy,” Forbes.com, May 8, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/lorenthompson/2017/05/08/eisenhowers-military-industrial-complex-shrinks-to-1-of-economy/

- Efraim Benmelech and Carola Fydman, “Military CEOs,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper (November, 2013).

- Mitra Toosi, “A Century of Change: the U.S. Labor Force, 1950–2050,” Monthly Labor Review (May 2002).

- Klaus Schwab, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution: What It Means, How to Respond,” World Economic Forum, January 14, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/

Additional Tools and Resources

To learn more about strategy activation, we recommend the following tools and resources: