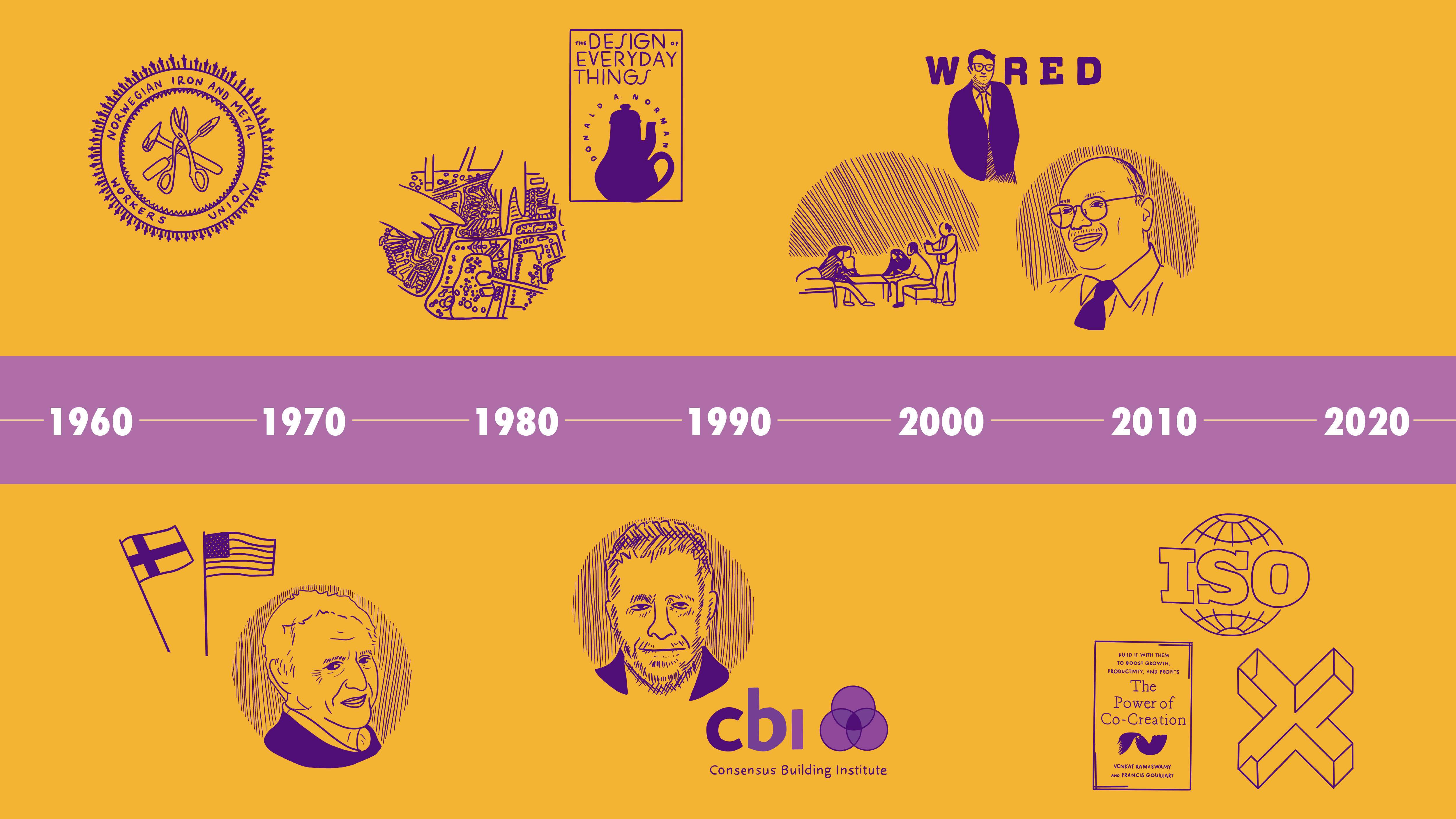

Co-Creation is a powerful concept: engaging broad stakeholders in a design or problem-solving process as co-designers. But where did it come from? Here’s a brief history of the idea, which remains emergent and evolving still today.

The History of Co-Creation

1960-70s

Trade unions in Scandinavia extend the workplace democracy movement into the right of workers to co-design IT systems that impact their job. They call this cooperative design.

1970s

Americans get interested in the “Scandinavian Approach” but think “cooperative” sounds too collectivistic, so they call it participatory design.

1971

John Heron coins the term collaborative inquiry to describe the importance of researching “with” rather than “on” people. Engaging end-users in research and insight gathering gains acceptance.

1980s

Participatory design extends from system design to other fields. Urban planners are early adopters, calling it collaborative placemaking or collaborative planning. They study the impact of the approach, citing improvements in efficiency, reduced blockages, and the magnitude of goals achieved.

1988

Don Norman coins the term user-centered design in his influential book Design of Everyday Things. This marks a shift from participatory design as an engineering mindset focused on requirements and tasks to a design mindset focused on holistic systems and human needs.

1990s

User-centered design evolves towards human-centered design and design thinking more broadly. Participatory design remains a more specific, focused strain within these movements. Since 1990, there has been a bi-annual Participatory Design Conference.

1993

Larry Susskind founds the Consensus Building Institute, launching a generation of professional negotiators steeped in the theory of collaborative dispute resolution that features co-creative activities such as joint fact-finding.

2000s

Studies performed on the outcomes of co-creation found participants in co-creative processes experienced increases in individual competence, support for the outcome, perceived legitimacy of process, and strengthened social networks.

2000

University of Michigan Professors CK Prahalad and Venkat Ramaswamy coin the term co-creation in their Harvard Business Review article Co-Opting Customer Competence. They go on to refine the concept in a series of books and articles, initially focusing on co-creation between customers and enterprises (similar to other emergent concepts like open innovation, collaborative innovation and customer-led innovation).

2006

Jeff Howe at Wired Magazine coins the term crowdsourcing, continuing the interest in breaking down barriers between consumers and enterprises in the interest of co-creation.

2010

In Ramaswamy’s 2010 book The Power of Co-Creation, he devotes a major section to co-creation among stakeholders within an organization, expanding the term beyond mere customer-enterprise value creation.

Also in 2010, an international standard on human-centered design is ratified: ISO 9241-210:2010. A major principle of the standard is “users are involved throughout design and development.”

2015

Co-creation is a mainstream term that encompasses prior concepts such as participatory design. Some define it strictly as co-design between enterprises and consumers, others, like XPLANE, apply co-creation to the inside of organizations, including the collaborative design of strategy, process and culture.

What’s next?

Just as design thinking has managed to expand the application of design principles from typical design challenges (like product design and interactive design) to problem-solving in general, co-creation is a rapidly expanding concept that will no longer refer to just enterprise-consumer co-design but to the co-design process of any group of stakeholders.

As all these terms converge, one distinction remains relevant. Methods like design thinking, human-centered design, and agile help us label how we answer the question HOW do we approach design? Co-creation answers the question WHO designs?

Even though design thinking and co-creation have a natural affinity, they hold different functions in describing a design approach. This explains how there are design firms who fervently espouse “design thinking” but do a lot of black-box studio concepting and then reveal their insights and concepts to clients and users. Likewise, fields as diverse as treaty negotiators, city planners, and social workers use co-creative principles without applying a design thinking methodology.

Maintaining co-creation as a powerful and distinct idea holds us to the standard of always asking ourselves who is the designer? and challenging us to broaden our expectations of who should be empowered to design.