If visual language is so universally and rapidly understood, why don’t we use it more often? Can this valuable skill be learned?

An extended trip to Germany in my late teens changed my world.

Before that experience abroad, I didn’t understand the value of literacy in another language. Like most Americans, I completed my high school language requirement of two years (French) without gaining any real competency.

But shortly after touching down in Berlin, I understood almost immediately that by learning German, a new world could be opened up that was previously closed to me. I was, for all intents and purposes, illiterate and impaired because I needed other people to translate or speak English in order to get by.

The Universal Language

I relate this story to emphasize the helplessness of those who don’t have the ability to communicate and the fact that language ties us together and opens up worlds that were previously closed to us.

So check this out: There is a universal language that everyone can read, a language that the human brain is hardwired to understand. In fact, a person’s understanding of this language occurs faster than any traditional written language and is retained longer, often by a factor of two or three.

I’m talking about visual language, the ability to communicate using pictures.

Humans have been communicating with each other for approximately 30,000 years, but we’ve been using words for only about 3,700 years. Because of this long history of communicating without text, our brains are simply hardwired to process visual information better and faster than we process text.1

Take my Germany example above for reference. Instead of landing on the ground illiterate as I did, with visual language it’s as though our brains come ready-made with a preloaded understanding of the language without us having to learn to read.

Children as Teachers

But there’s a catch. Although everyone comes with a ready-made ability to read and understand visual language, we are overwhelmingly illiterate when it comes to composing or writing in visual language.

When learning a foreign language, speakers progress from oral, to written, to compositional fluency. One can think of this as a progression from being able to understand, speak, read, and eventually write and create using that language.

When it comes to visual literacy, most people are stuck in the juvenile state of being able to read, but completely unable to compose or create visually. How do we overcome this deficit?

We can learn a lot from our children.

Children instinctively draw as a means to explore and understand their world. This is a natural outgrowth of their already highly developed ability to read and make sense of visual stimuli. But most educational systems begin to deemphasize or completely drop drawing as a method of exploration and problem-solving as soon as kids begin learning reading, writing, and mathematical skills (more on this for another blog post). Therefore, children’s growth and ability to gain fluency in visual language is stunted around age 6, and very few continue past that point.

Start With the “ABCs”

So, where does a person start learning to communicate visually, knowing that they stopped practicing so many years ago?

Start with the alphabet.

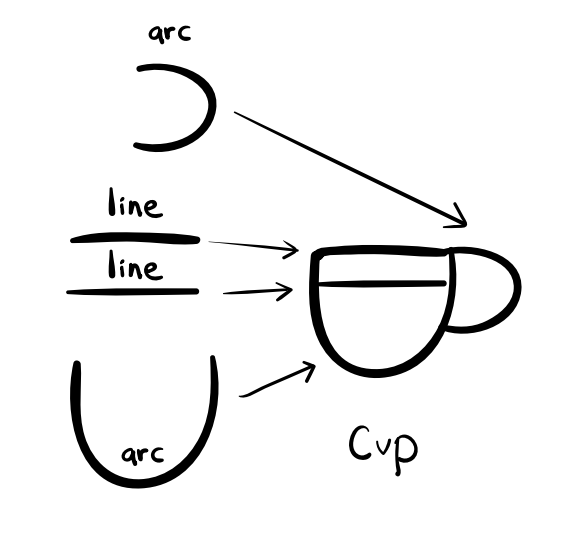

In the same way we learn written languages by learning the set of symbols used to compose words, we can learn visual language by breaking down visual marks into a core set of glyphs—hieroglyphic characters or symbols—that can be combined to create just about any object, action, or interaction.

Learning the visual alphabet is a great first step in becoming visually literate, and there’s lots more to learn.

I’ve put together a quick list of things I recommend to help you build real compositional fluency:

- Challenge yourself to see how many everyday objects you can draw using only the 12 shapes you see in the visual alphabet.

- Bring paper or a sketchbook to meetings and try to use more pictures than words as you take notes.

- When creating presentations, try to rely more on pictures than words.

- Think in terms of telling a story. Who is the hero? What is their journey? What is the conflict? What is the lesson?

- Look for generally understood frameworks that will help people recognize and align around your idea.

- Experiment with different markers and pens, and see what helps you make nice, meaningful marks.

- As you work with people, listen for descriptions of process. For example, “First ‘x’ happens, which leads to ‘y,’ and then it is sent to Jeannie, who does ‘z.’” Then draw each of these actions and connect them with arrows.

- Always label your drawings so others can quickly make sense of them.

1 LivePlan, June 14, 2018, Noah Parsons, https://www.liveplan.com/blog/scientific-reasons-why-you-should-present-your-data-visually/