Connect to Learn

Related Posts:

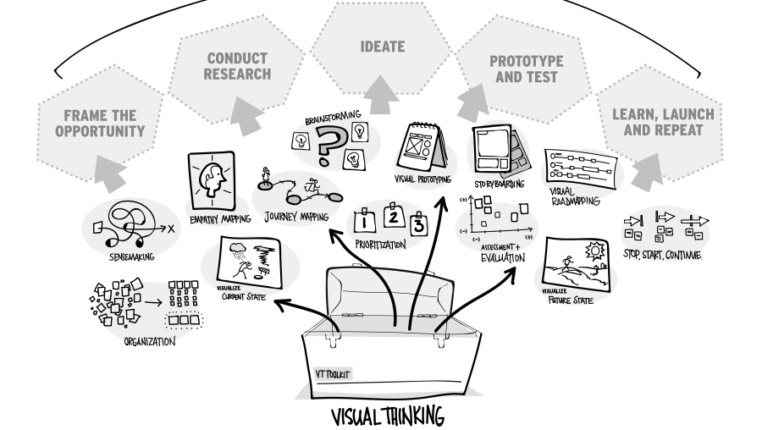

Design Thinking vs. Visual Thinking

Design Thinking vs. Visual Thinking

Responding Effectively to Rapid and Unexpected Change

Responding Effectively to Rapid and Unexpected Change

XPLANE’s Top 25 Tips and Tricks for Remote Collaboration

XPLANE’s Top 25 Tips and Tricks for Remote Collaboration

Date:

April 6, 2020

April 6, 2020

Author:

Jason Young

Jason Young